1. Introduction

Maternal health is defined as the health of a woman during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period (WHO, 2012). Maternal health is one of the priority areas of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.1, which aims to decrease the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to

below 70 deaths per 100,000 births. MMR refers to the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (Comfort, 2016; Girum & Wasie, 2017). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest MMR. The region

had 179,000 out of 289,000 global deaths in 2014 (WHO, 2014). As a result, developmental organisations have introduced maternal mHealth interventions to provide maternal-related information to maternal healthcare clients in rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa where most of these deaths occur (Blauvelt et al., 2018). For instance, mHealth interventions may send maternal healthcare clients tips on maternal healthcare and reminders to visit antenatal clinics through short message service (SMS) and voice messages. mHealth interventions have the potential to promote health seeking behaviour and health facility usage for prenatal care, delivery and postnatal care, which

is essential for better maternal health outcomes (Sowon & Chigona, 2021). mHealth involves the use of mobile devices such as mobile phones for health (Noordam et al., 2011). In rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, mHealth is challenged due to low mobile phone ownership (Sondaal et al., 2016). In rural areas, there is disparity in mobile phone ownership. For example, in Malawi and Ethiopia there is a disparity of 26% and 46%, respectively (Rheault & Mccarthy, 2016). In Malawi, low literacy levels and poverty in rural areas affects access and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). In the villages of Malawi, traditional methods of communication, such as word-of-mouth, village messengers, and village headmen are the preferred way to convey messages (Marron et al., 2020). Low levels of literacy and lack of ICTs, such as mobile phones, make these the traditional methods of communication common in rural areas (Marron

et al., 2020), In Sub-Saharan Africa, women are 15% less likely to own a mobile phone than their male counterparts (Handforth & Wilson, 2019). Consequently, women who do not own mobile phones may

not have direct access to mHealth interventions, as well as other mobile phone mediated developmental interventions. Therefore, for maternal healthcare clients to access maternal mHealth intervention, it is likely that these clients negotiate mobile phone access and usage from owners of mobile phones in their communities. Some studies have shown that people negotiate with one another all the time in every aspect of life (Patton & Sundar Balakrishnan, 2012; Zohar, 2015). Other studies have found that social norms may be routinised due to the negotiated agency of those processes in institutions (Giddens, 1984; Ling et al., 2020), such as in health service provision institutions (Ling et al., 2020). In other circumstances, marginalised women have used mobile phones to negotiate harassment issues in the work environment (Pei et al., 2022). Negotiation is referred to as “a form of decision making in which two or more parties talk with one another in an effort to resolve their opposing interests” (Lewicki et al., 2016). One of the reasons why negotiation occurs is to agree on how to share limited resources (Lewicki et al., 2016), In poor resource settings, where households may have only one family member owning a mobile phone, other family members may negotiate usage of the mobile phone (NSO & MACRA, 2014). For maternal mHealth, negotiating mobile phone usage could be possible with family members and community

members for whom the maternal healthcare client finds trustworthy (Maliwichi & Chigona, 2022a). It could be the case that maternal health is associated with cultural norms, which may prohibit the maternal healthcare client from negotiating mobile phone usage for maternal-related issues with anybody. Moreover, pregnancy is associated with taboos, where there could be specific people that maternal healthcare clients may negotiate usage of their mobile phone for maternal-related issues (Nyemba-Mudenda & Chigona, 2018). A few studies in maternal mHealth have reported on the negotiation process of mHealth use in

maternal healthcare, where maternal healthcare clients aimed to make their use of mHealth, a culturally appropriate behaviour (Sowon & Chigona, 2021). Most studies in maternal and reproductive mHealth explained the importance of negotiating cost of mHealth solution with mobile network operators when implementing mHealth solutions for reproductive health (Mangone et al., 2016; Prinja et al., 2018; WHO, 2015). However, little is known about how maternal healthcare clients who lack prerequisite technologies such as mobile phones negotiate usage of mobile phones for maternal mHealth (Larsen-cooper et al., 2015; Maliwichi et al., 2021). Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following research question: How do maternal healthcare clients who do not own mobile phones negotiate use of mobile phones for maternal mHealth interventions? To answer the research question, we used a case study of Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF) (which means Health Centre by Phone) maternal mHealth intervention. CCPF was launched in 2011 in Malawi as a maternal and child health mHealth intervention in one of the poorest performing district in maternal health (VillageReach, 2017). The intervention allows maternal healthcare clients who do not own mobile phones to use mobile phones of family members and other community members. In addition, the intervention recruited community volunteers and provided them with mobile phones to facilitate access and usage of the maternal mHealth intervention by maternal healthcare clients who do not own mobile phones (Larsen-cooper et al., 2015). The rest of the paper is organised as follows: the next section is literature review, which highlight the concept of negotiation, negotiations in mHealth and maternal mHealth interventions. Literature

review is followed by case description of Chipatala Cha Pa Foni. In this section, the Malawi profile is described and then the CCPF mHealth intervention. The methodology section presents the data collection and analysis methods used in this study. In this section, ethical considerations are also highlighted, and the findings section follows. The section presents negotiating tactics used by maternal healthcare clients to negotiate mobile phone usage, followed by analysis, discussion and conclusion. Lastly, study limitation and future work are highlighted.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Maternal health and mHealth interventions

Maternal Health is one of the areas that have received support in the development of mHealth interventions to combat maternal deaths. For example, MomConnect in South Africa, Rapid SMS in Rwanda and CCPF in Malawi (Blauvelt et al., 2018; Ngabo et al., 2012; Seebregts et al., 2016).

Maternal mHealth interventions use SMSs and toll-free hotlines for maternal healthcare clients to receive tips on maternal-related issues and reminders to visit antenatal clinics for vaccinations, medications and routine checkups (Crawford et al., 2014; Willcox et al., 2019). Furthermore, the tollfree hotline enables the maternal healthcare clients to call and ask maternal related help and advice (Larsen-cooper et al., 2015).

Studies in maternal mHealth have found that maternal mHealth interventions promotes the health seeking behaviour among maternal healthcare clients (Blauvelt et al., 2018; Sowon et al., 2022).

Consequently, maternal mHealth interventions improve maternal health outcomes. Therefore, it is essential to promote the use of maternal mHealth interventions for all maternal healthcare clients, regardless of whether or not they own a mobile phone (Maliwichi & Chigona, 2022b).

2.2 The concept of negotiation

Negotiations happen every day in our societies. Even though people associate the concept of negotiation in the world of business or politics (Zohar, 2015); negotiations also happen in our homes, at school, and even at the hospital. Children negotiate with their parents how chores and assignments ought to be done at home. Students could also negotiate the due dates of their assignments with their lectures. In all these contexts, main aim of negotiation is to reach a consensus where the negotiating partners reach an agreement (Lewicki et al., 2016). This could be due to the fact that people depend on each other, and negotiations are used to manage situations. In addition, negotiations can be used to resolve conflicts (Lewicki et al., 2016) and change institutional processes (Ling et al., 2020).

• Negotiating tactics or strategies

In negotiations, there are different strategies or tactics that negotiators could use during negotiations (Lewicki et al., 2016). These include yielding or accommodating, inaction (also called avoiding), and compromising. Negotiators practicing accommodating tactic does not have interest whether they would gain their own outcomes, but rather are interested in whether the other party attains his or her outcomes. This involves lowering one’s own aspirations to let the other win. Partners practicing inaction as a tactic show little interest in whether they attain their own outcomes, as well as in how the other party obtains their desired outcomes. This could mean that the parties are doing nothing or they have withdrawn from negotiations. Compromising tactics are a conflict management strategy. Here one negotiating partner exerts little effort to achieve their outcomes, but exerts moderate effort to help the other party achieve their outcomes.

• Importance of negotiating skills

Negotiating skills can be in-born. For example, children negotiate with their parents all the time at home. Others have to learn to negotiate due to the nature of their job. Regardless of whether one has an in-born negotiating skill or not, it is important for people to have negotiating skills considering the interdependent nature of the society. Studies have highlighted the importance of enhancing negotiating skills in people (Roloff et al., 2003; Sadki & Bakkali, 2015). Others have published practical guides on how to enhance negotiating skills. For example, there are guidelines which aid implementers of mobile application solutions on how to negotiate with mobile network operators on the cost of implementing affective mHealth solutions (Crawford et al., 2014; WHO, 2015). Therefore, it is important to negotiate in every aspect of life.

2.3 Negotiations in mHealth

Negotiations in mHealth happen at various stages of the development of the mobile applications. For instance, mHealth developers and stakeholders of mHealth negotiate different aspects of mHealth.

mHealth developers may negotiate with potential users of mHealth; for example, what functions ought to be present in mobile health application (Giunti, 2018). On one hand, these negotiations happen during the planning and development phase of the mHealth application (Vickery, 2015). On the other hand, negotiations could also happen during mHealth policy formulations, considering the sensitiveness of health data (Sadki & Bakkali, 2015). Hence, policy makers ought to negotiate health data usage with mHealth implementers. Others have highlighted the importance of negotiating how Smartphone companies may use personal data derived from health application. Users use mobile application for health on their Smartphones, for instance, measuring their blood pressure without knowledge that this data may be sold by mobile phone manufactures (Faulkner, 2018). This is not acceptable, and there ought to be a clear distinction between health (which is a personal right and also things that benefit society as a

whole) and consumer goods bought and sold for profit-making purposes (Faulkner, 2018). Therefore, there ought to be a negotiation-based approach to resolving issues concerning the privacy policy conflicts in mHealth (Sadki & Bakkali, 2015).

2.4 Negotiations in maternal mHealth intervention

In maternal mHealth intervention, the concept of negotiation has been highlighted twofold: on the one hand, mHealth implementers have negotiated the cost of delivering short message services (SMSs) to maternal healthcare clients (Larsen-Cooper et al., 2015; WHO, 2015). In other circumstances, mHealth implementers have negotiated the cost of calls with mobile service providers for maternal mHealth interventions (Crawford et al., 2014; Mangone et al., 2016). These negotiations have led to the provision of toll-free hotlines and free SMS delivery to maternal healthcare clients (Crawford et al., 2014). Moreover, collaborations with different stakeholder in an mHealth project could have an impact in successful negotiations, which could also lead to scaling-up of interventions (Blauvelt et al., 2018). On the other hand, maternal healthcare clients have negotiated maternal mHealth use. In contexts where pregnancy is surrounded by social-cultural norm, maternal healthcare clients have to negotiate usage of maternal mHealth interventions. This could be due to the fact that the use of mHealth ought to be culturally appropriate given the interdependent nature of maternal healthcare-seeking behaviour

(Sowon & Chigona, 2021). Theories have also highlighted on the importance of appropriate technology use, for instance, the compatibility concept in the diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers,

2003). Therefore, it is important to negotiate appropriate use of maternal mHealth considering the sensitivity of maternal issues. However, there is still dearth of literature on how those who lack

prerequisite technologies negotiate use of maternal mHealth interventions (Maliwichi & Chigona, 2022a).

3 Case Description of Chipatala Cha Pa Foni

3.1 Malawi Profile

CCPF is an mHealth intervention running in Malawi. Malawi is a country in Southern Africa with a population of about 17,563,749 million people (National Statistics Office (NSO), 2018). About 85.6% of this population resides in rural areas of the country (National Statistics Office (NSO), 2018). CCPF was piloted in 2011 in four rural catchment areas of Balaka District as a maternal and child health intervention. Balaka District was selected due to its lowest maternal and child health indicators in the southern region of Malawi.

The healthcare system in Malawi is organised into four levels, namely: community, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels (MoH, 2022). All these levels are linked through an established referral

system. The District Health Officer (DHO) is in-charge of community, primary, and secondary levels, which are at the district level. The health system in Malawi is challenged with limited human resource

for health, such as doctors, nurses, and clinical officers. This has been attributed to the migration of health professionals, and death due to HIV/AIDS. The doctor-patient ratio, stands at 1 to 48000, which is one of the lowest in the region (Kawale et al., 2019). This low ratio extends to other health professionals, such as nurses and HSAs (Lutala & Muula , 2022), contributing to poor health outcomes. Consequently, this also contributes to poor maternal health outcomes.

3.2 Chipatala Cha Pa Foni mHealth intervention

CCPF is a toll-free health hotline in Malawi that creates a link between the health centre and remote communities. It has trained health workers, who provide information and referrals over the phone (Innovation Working Group (IWG), 2016). Initially, users could also opt for personalised voice and SMS health messages tailored to women regarding their pregnancy or the health needs of their children (Innovation Working Group (IWG), 2016). The personalised voice and SMS health messages have now been replaced with on demand IVR messages. Remote rural communities in Malawi, as in

other developing countries, face challenges such as long distances to the health facility, which prevents people from seeking healthcare. The CCPF maternal mHealth intervention was introduced to improve healthcare-seeking behaviour and healthcare utilisation. By 2018, CCPF was scaled-up to all districts in Malawi and is now fully owned by the Government of Malawi (VillageReach, 2018).

3.3 Community volunteers of CCPF

The implementing agency recruited community volunteers in communities of Balaka District to act as agents of CCPF. These community volunteers were trained on how to use CCPF and provided

with a mobile phone. The volunteers were encouraged to sensitise communities by visiting maternal healthcare clients door-to-door, as well as during social gathering in their communities (Watkins et

al., 2013). Maternal healthcare clients who do not own mobile phones were encouraged to use mobile phones of community volunteers, other community members, and family members. This made CCPF

accessible to maternal healthcare clients regardless of their mobile phone ownership status.

4. Methodology

The study employed qualitative research methods, a single case study research design and interpretive paradigm. Qualitative research methods were more appropriate to explain how maternal clients who do not own mobile phones negotiated mobile phone access and usage of the mHealth intervention. Furthermore, qualitative research methods proved significant in preventing the loss of context. The study bounded the case using the context and the activity, thereby making the case study more appropriate.

4.1 Data collection

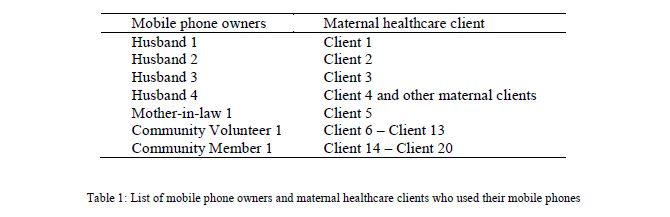

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs). We interviewed seven mobile phone owners and seven maternal healthcare clients. These mobile phone owners and maternal health care pairs were geographically dispersed and it was not economically feasible to visit each pair separately. Hence, we opted for telephone interviews, and telephone calls recorded using callX mobile application. Table 1 lists the mobile phone owners and the maternal

healthcare clients who used their mobile phones.

We conducted two FGDs (of eight and seven maternal healthcare clients, respectively) in two catchment areas, with the help of a community volunteer and a community member. These mobile phone owners had several maternal healthcare clients using their mobile phone for CCPF. Due to covid-19 travel restrictions, we were unable to travel and conduct the interviews in June 2020. Therefore, we opted for telephonic FGDs with the help of the maternal healthcare clients, community volunteer and community member, as the owners of the mobile phones. We asked the mobile phone owners to find a quiet place and put the mobile phone on loudspeaker and be moderators of the discussion. The discussion was recorded using callX mobile application.

4.2 Data Analysis

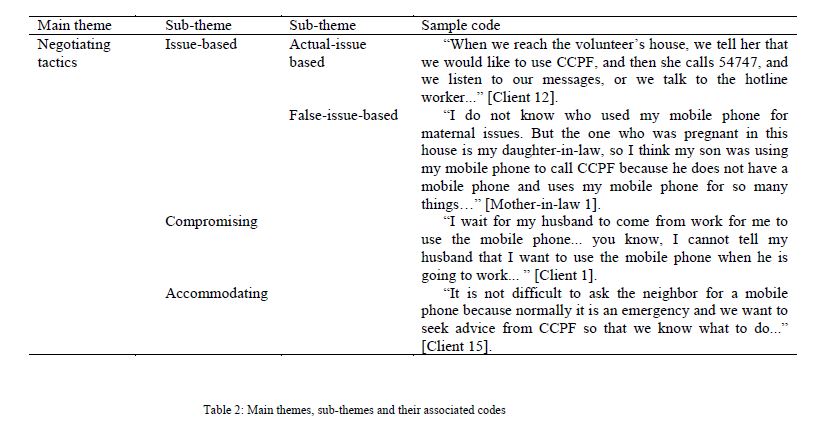

The collected data was transcribed in Chichewa and was later translated into English. English transcripts were then imported into Nvivo 12 for data analysis. We used inductive thematic data analysis to analyse the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Table 2 shows the sample themes and their associated codes.

4.3 Ethical considerations

We obtained permission to conduct the study in Balaka District from the Balaka District Health Office, as well as the Malawi Ministry of Health and the mHealth implementing agency, VillageReach. We also got ethical clearance from the National Health Sciences Research Committee in Malawi. Consent was sought to interview the participants and issues of privacy and confidentiality were discussed. It was clarified to participants of FGDs that it was difficult to ensure that what will be discussed remain confidential, due to the nature of the discussion. Even, though the study was more about negotiating usage of mobile phone, we did not recruit pregnant women. This was the case in order to mitigate the risks associated with pregnancy, in such case where a participant recalls a traumatic experience. We anonymised the participants using the code Client x and Husband x,

Community member or Volunteer x.

5. Findings

In maternal mHealth intervention, access to mobile phones by the intended users is crucial for the success of the intervention. Even though the maternal healthcare clients in this study did not own mobile phones, they accessed mobile phones through different mobile phone owners, such as family relations (husbands and mothers-in-law), community volunteers, and community members.

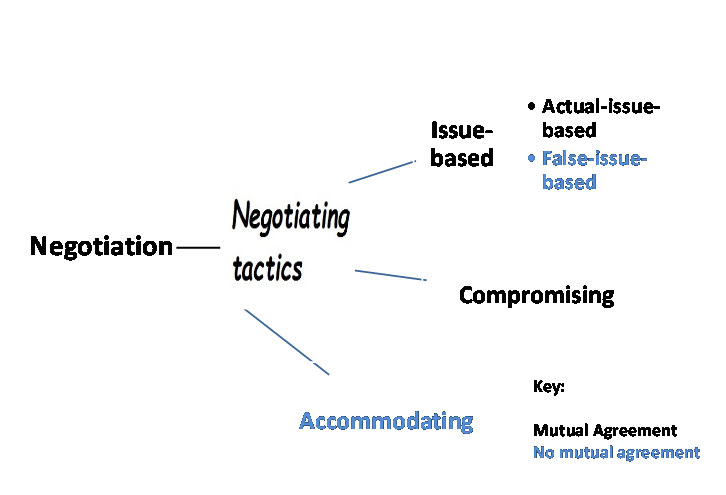

Maternal healthcare clients in this study negotiated mobile phone usage from mobile phone owners to use maternal mHealth intervention. The findings of this study suggest that maternal healthcare clients used cooperative tactics to negotiate usage of the mobile phone, rather than

competitive tactics. Cooperative tactics are tactics that create value by satisfying the interests of all the parties involved, for example willingness to compromise, and having flexible usage terms. These

tactics could be categorised further as: 1) issue-based tactics; 2) compromising tactics; and 3) accommodating tactics.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for negotiating technology use

5.1 Issue-based tactic

Maternal healthcare clients in this study used issue-based tactic to negotiate mobile phone usage. Issue-based negotiation tactics refer to a way of handling one or more negotiation issues in pursuit of

a joint or individual goal (Geiger, 2017). Maternal healthcare clients in this study used two ways of issue-based tactic: 1) by using the actual issue, which is to call CCPF for maternal-related issue; and

2) using a different issue to negotiate usage of a mobile phone. These two tactics have been conceptualised further as actual-issue-based tactics, and false-issue-based tactics.

• Actual-issue-based tactic

Most maternal healthcare clients in this study used the actual-issue-based tactics to negotiate usage of a mobile phone. This was apparent when the maternal healthcare client and mobile phone owner had a mutual agreement that the maternal healthcare client could use their mobile phone for maternal related issue.

“When we reach the volunteer’s house, we tell her that we would like to use CCPF, and then she calls 54747, and we listen to our messages, or we talk to the hotline worker...” [Client 12].

This form of agreement was common between maternal healthcare clients and a dedicated mobile owner. In this case, the maternal healthcare clients trusted the mobile owner, because the mobile

owner showed interest in the maternal healthcare client’s health and welfare, and took privacy issues about the maternal healthcare client seriously. In Malawi, as well as other African countries, maternal

healthcare clients do not just talk about their pregnancy-related issues with ease. Pregnancy is a sensitive topic that is discussed only with someone who can be trusted (Ngomane & Mulaudzi, 2012).

• False-issue-based tactic

Some maternal healthcare clients in this study used false-issue-based tactics of negotiation. We define false-issue-based tactics of negotiation as bargaining of mobile phone usage for an issue, but

using the mobile phone for another purpose.

“I do not know who used my mobile phone for maternal issues. But the one who was pregnant in this house is my daughter-in-law, so I think my son was using my mobile phone to call CCPF because he does not have a mobile phone and uses my mobile phone for so many things…” [Mother-in-law 1].

It is possible that the maternal healthcare clients negotiated usage of the mobile phone for something else, while simply using the mobile phone for maternity-related issues.

5.2 Compromising tactic

The findings of this study suggest that maternal healthcare clients used compromising negotiation tactics when negotiating mobile phone usage. Compromising negotiation tactics usually happens in a win-lose situation (Schmidt & Cross, 2014). Compromising tactics prove to be one of the most basic negotiation tactics where both parties give up something that they want in order to get something else they want more. In this study, maternal healthcare clients had to use concession in order to reach mobile phone usage times with their husbands.

“I wait for my husband to come from work for me to use the mobile phone... you know, I cannot tell my husband that I want to use the mobile phone when he is going to work ...” [Client 1].

One of the husbands narrated that sometimes, he agreed with his wife on the times both could listen to the messages about pregnancy, or on the times both could talk to the doctor. Compromising negotiation tactics were also more prominent between maternal healthcare clients and community volunteers. A community volunteer mentioned that, when maternal healthcare clients were more advance in their pregnancy and could not travel long distances to access mobile phones, a community volunteer would instead visit them at their homes.

When using compromising tactics, normally negotiating partners work together to find an acceptable middle ground that works for both of them (Schmidt & Cross, 2014). In maternal mHealth, compromising tactics are very important, as both maternal healthcare clients and husbands or community volunteers want to achieve better maternal outcomes.

5.3 Accommodating tactic

The findings of this study suggest that accommodating negotiation tactics was prevalent when maternal healthcare clients were using community members such as neighbours to negotiate mobile phone access.

“It is not difficult to ask the neighbor for a mobile phone because normally it is an emergency and we want to seek advice from CCPF so that we know what to do...” [Client 15].

In this case, no formal agreement was necessary for long-term use, but the maternal healthcare client trusted that the neighbour would allow her to use the mobile phone and the neighbour usually

accommodated their request. This could be a social norm in villages where people share resources in times of need (Vickery, 2015).

6. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that the mobile phone owners played a greater role when maternal healthcare clients were negotiating the use of the mobile phone. This could be attributed to the importance of the issue being negotiated for, in this case, maternal health. In addition, health related issues could be prioritised over personal issues when negotiating mobile phone usage. Therefore, this study highlights: 1) the importance of accommodating beneficiaries of mHealth through technology sharing; 2) when to use bogey or false issue issue over the actual issue; and 3) the role of communities of purpose in promoting access to technologies.

6.1 The importance accommodating beneficiaries of mHealth through technology sharing

In poor-resource settings, beneficiaries of mHealth who do not own mobile phones tend to negotiate mobile phone usage when an emergency occurs. For maternal health, this could be that a maternal healthcare client is in pain and has no idea why this is the case. Sometimes, this could mean saving someone’s life. Therefore, it is important for mobile phone owners to accommodate beneficiaries of mHealth or their guardians request to use their mobile phones.

In this study, mobile phone owners used accommodating tactics when maternal healthcare clients negotiated mobile phone usage. An accommodating tactic tends to be more concerned with the cooperativeness of the parties involved (McCracken et al., 2008). Basically, this is a win-lose situation (Coburn, 2013), where “One way to generate alternatives is to allow one person to obtain their objectives and compensate the other person for accommodating their interests” (Lewicki et al., 2016). In this study, community members played the losing partner for accommodating tactics to work for maternal healthcare clients. In maternal health, community members may sacrifice their time in favour of the maternal healthcare client, who may want help at that particular time. Timely access to maternal health information has the potential to serve the lives of the mother and her unborn child. For some community members, this proved to be a way of winning over maternal healthcare clients to use healthcare service during pregnancy.

In this study, accommodating tactics may have worked due to umunthu philosophy, which is practiced in most poor-resource communities of Malawi (Zamani & Sbaffi, 2020), wherecommunities value mutuality and reciprocity (Bandawe, 2005). Therefore, it is important for mHealth

implementers to sensitise communities to the importance of sharing resources in times of need. Other studies have found that communities that practice a sharing culture, it is a norm in these communities

to accommodate beneficiaries of mHealth who lack prerequisite technologies such as mobile phones (James, 2011; Tran et al., 2015). In turn, the beneficiaries feel free to negotiate mobile phone usage

from any mobile phone owner.

6.2 False-issue or actual-issue negotiating tactic: which is appropriate?

Health is a complex phenomenon. Health issues tend to be private. In most cases, mHealth beneficiaries of diabetes or sexually transmitted diseases, for example, would not want anyone to know their health concerns. Maternal health is even more complex, since it is associated with cultural beliefs. On the one hand, beneficiaries of mHealth who do not own mobile phones in this study tend to use false-issue negotiating tactic when negotiating mobile phone usage. This was more prevalent

when the maternal healthcare client did not trust the mobile phone owner, or the mobile phone owner was young. Some studies have found that people may employ “bogey” tactics, which involve exaggerating the

importance of a given issue (Lewicki et al., 2016). False-issue-based tactics and bogey tactics could be successful, as long as the truth is not revealed (Geiger, 2017). In maternal health, using false issuebased

could happen due to the sensitive nature of maternity-related issues in a rural setting. Maternal healthcare clients treat maternity-related issues as private (Fagbamigbe & Idemudia, 2015).On the other hand, beneficiaries of mHealth use the actual-issue-based tactic to negotiate usage of the mobile phone. This was due to the fact that the beneficiary of mHealth and the mobile phone owner had a mutual agreement with the mobile phone owner or the mobile phone was a project mobile phone or government-issued mobile phone, for the purposes of maternal and child health intervention (Larsen-cooper et al., 2015; Ngabo et al., 2012). Furthermore, actual-issue-based tactics are easier to use when a mobile phone belongs to maternal healthcare clients’ significant other (Carret al., 2021). Regardless of the circumstances of the beneficiaries of mHealth, using an actual-issue-based tactic could be more appropriate, due to the fact that, when false-issue-based tactics or bogey tactics are discovered, people will question the behaviour of the negotiators in this regard. A study in negotiation

has also suggested that it is important to negotiate using an important issue first, when using issue based negotiation tactics (Geiger, 2017). For example, it is important to negotiate mobile phone usage for maternity-related issues first, and later for personal or other concerns. However, certain studies have found that simultaneous bargaining could be beneficial (Patton & Balakrishnan, 2010; Patton & Sundar Balakrishnan, 2012).

6.3 The role of communities of purpose in promoting access to

technologies

A community of purpose (CoP) is understood as a community of people who are going through a similar process or are trying to achieve a similar objective (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020). In this study, CoP comprised of family members, community members, community volunteers, and community health workers. CoP played a greater role in providing access of mobile phones to mHealth beneficiaries. The findings of this study suggest that CoP used compromising negotiating tactics when mHealth beneficiaries were negotiating the use of their mobile phones. A community volunteer mentioned that when maternal healthcare clients were more advance in their pregnancy and could not

travel long distances to access the mobile phone, where a community volunteer would instead visit them at their homes. When using compromising tactics, normally negotiating partners work together to find an acceptable middle ground that works for both of them (Schmidt & Cross, 2014). Studies on negotiation have found that prior relationships between negotiating parties influence compromising tactics (McCracken et al., 2008; Schmidt & Cross, 2014). Moreover, this relationship makes negotiation a bit easier for the maternal healthcare client themselves (Zohar, 2015). In maternal mHealth, compromising tactics are very important, as both maternal healthcare clients and CoP members want to achieve better maternal outcomes; thereby reducing MMR (Sowon & Chigona, 2021). In addition, CoP plays a greater role in reducing the digital divide, which is greater among women (Maliwichi et al., 2021). Moreover, CoP has the potential to enhance the digital skills

of mHealth beneficiaries who lack prerequisite technologies by training them on how to use the technology (Larsen-cooper et al., 2015). Access to information has the potential to promote healthy living styles, which could promote sustainable development in rural areas.

7. Conclusions

Negotiating mobile phone usage for health has the potential to promote the health and wellbeing of mHealth beneficiaries who lack prerequisite technologies, such as mobile phones. In addition, negotiating mobile phone usage by mHealth beneficiaries who lack prerequisite technologies has the potential to improve their digital skills. The study noted that mHealth beneficiaries who do not own mobile phones used several negotiating tactics to negotiate mobile phone usage, and these include: 1) issue-based negotiating tactic; 2) compromising negotiating tactic; and 3) accommodating negotiating tactic. This study may inform policymakers and mHealth implementers on how mHealth beneficiaries

who lack prerequisite technology may negotiate usage of technologies. Furthermore, mHealth implementers ought to sensitise the roles of CoP in communities, since they play a greater role in reducing the digital divide gap and promoting an inclusive environment.

8. Limitations of the study and future work

The study was limited in using only a single case study. Therefore, future work may test the conceptual framework in similar settings. Furthermore, the conceptual framework could be tested in other sectors, such as education.

References

Bandawe, C. R. (2005). Psychology brewed in an African pot: Indigenous philosophies and the quest for relevance. Higher Education Policy, 18(3), 289–300.https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300091

Bhattacharyya, S., Basak, J., Bhaumik, P., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2020). Cultivating online virtual community of purpose to mitigate knowledge asymmetry and market separation of rural artisans in India. In D. Junio & C. Koopman (Eds.), Evolving Perspectives on ICTs in Global Souths.

IDIA 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science (Vol. 1236, pp. 201–215).

Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52014-4_14

Blauvelt, C., West, M., Maxim, L., Kasiya, A., Dambula, I., Kachila, U., Ngwira, H., & Armstrong, C. (2018). Scaling up a health and nutrition hotline in Malawi: The benefits of multisectoral collaboration. BMJ, 363, k4590. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4590

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carr, R. M., Quested, E., Stenling, A., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Prestwich, A., Gucciardi, D. F., McVeigh, J., & Ntoumanis, N. (2021). Postnatal Exercise Partners Study (PEEPS): a pilot randomized trial of a dyadic physical activity intervention for postpartum mothers and a

significant other. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 251–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.1902815

Coburn, C. (2013). Negotiation Conflict Styles. Harvard Medical School.https://karemmieses.com/wpcontent/uploads/sites/10042/2019/08/NegotiationConflictStyles.pdf Comfort, A. B. (2016). Long-term effect of in utero conditions on maternal survival later in life:evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Population Economics, 29(2), 493–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0581-9

Crawford, J., Larsen-Cooper, E., Jezman, Z., Cunningham, S. C., & Bancroft, E. (2014). SMS versus voice messaging to deliver MNCH communication in rural Malawi: Assessment of delivery success and user experience. Global Health Science and Practice, 2(1), 35–46.

https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D- 13-00155 Fagbamigbe, A. F., & Idemudia, E. S. (2015). Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: Evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming. BMC Pregnancy and

Childbirth, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0527-y

Faulkner, A. (2018). Blood Informatics: Negotiating the Regulation and Usership of Personal Devices for Medical Care and Recreational Self-monitoring. In R. Lynch & C. Farrington (Eds.), Quantified Lives and Vital Data. Health, Technology and Society. Palgrave Macmillan.

https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95235-9_9 Geiger, I. (2017). A model of negotiation issue–based tactics in business-to-business sales

negotiations. Industrial Marketing Management, 64, 91–106.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.02.003

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

Girum, T., & Wasie, A. (2017). Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology, 3(1), 19.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-017-0059-8

Giunti, G. (2018). 3MD for Chronic Conditions, a Model for Motivational mHealth Design: Embedded Case Study. JMIR Serious Games, 6(3), e11631. https://doi.org/10.2196/11631

Handforth, C., & Wilson, M. (2019). Digital Identity Country Report: Malawi. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wpcontent/uploads/2019/02/Digital-Identity-Country-Report.pdf

Innovation Working Group (IWG). (2016). CHIPATALA CHA PA FONI:Healthcare Through Mobile Phones. https://www.villagereach.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CCPF-Case-Study-UNFoundation.pdf

James, J. (2011). Sharing mobile phones in developing countries: Implications for the digital divide.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(4), 729–735.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.11.008

Kawale, P., Pagliari, C., & Grant, L. (2019). What does the Malawi demographic and health survey say about the country’s first health sector strategic plan? Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010314

Larsen-Cooper, E., Bancroft, E., Rajagopal, S., O’Toole, M., & Levin, A. (2015). Scale Matters: A Cost-Outcome Analysis of an m-Health Intervention in Malawi. TELEMEDICINE and EHEALTH,22(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0060

Larsen-cooper, E., Bancroft, E., Toole, M. O., & Jezman, Z. (2015). Where there is no phone: The benefits and limitations of using intermediaries to extend the reach of mHealth to individuals

without personal phones in Malawi. African Population Studies Special Edition, 29(1), 1628–1642. https://doi.org/10.11564/29-1-714

Lewicki, R. J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D. M. (2016). Essentials of Negotiations (6th ed.). McGraw Hill Education.

Ling, R., Poorisat, T., & Chib, A. (2020). Mobile phones and patient referral in Thai rural healthcare: a structuration view. Information Communication and Society, 23(3), 358–373.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1503698 Lutala, P., & Muula, A. (2022). Brief behaviour change counselling in non-communicable diseases in Mangochi, Southern Malawi: A hypothetical acceptability study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 8(68), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-01032-0

Maliwichi, P., & Chigona, W. (2022a). Towards a Framework on the Use of Infomediaries in Maternal mHealth in Rural Malawi. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge and Management, 17, 387–411. https://doi.org/10.28945/5015

Maliwichi, P., & Chigona, W. (2022b). Factors affecting the use of infomediaries in mHealth interventions: Case of maternal healthcare in rural Malawi. NEMISA Summit and Colloquium 2022, 1–30.

https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/28698/DigitalSkill2022Proceedings.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=29

Maliwichi, P., Chigona, W., & Sowon, K. (2021). Appropriation of mHealth Interventions for Maternal Healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa: Hermeneutic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth,9(10), e22653. https://doi.org/10.2196/22653

Mangone, E. R., Agarwal, S., Engle, K. L., Lasway, C., Zan, T., Beijma, H. Van, Orkis, J., & Karam,

R. (2016). Sustainable Cost Models for mHealth at Scale : Modeling Program Data from m4RH Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0148011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148011

Marron, O., Thomas, G., Burdon Bailey, J. L., Mayer, D., Grossman, P. O., Lohr, F., Gibson, A. D.,Gamble, L., Chikungwa, P., Chulu, J., Handel, I. G., De C Bronsvoort, B. M., Mellanby, R. J.,& Mazeri, S. (2020). Factors associated with mobile phone ownership and potential use for

rabies vaccination campaigns in southern Malawi. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 9:62, 1–11.https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00677-4

McCracken, S., Salterio, S. E., & Gibbins, M. (2008). Auditor-client management relationships and roles in negotiating financial reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(2008), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.09.002

MoH. (2022). The health care system. Republic of Malawi.

https://www.health.gov.mw/index.php/2016-01-06-19-58-23/national-aids National Statistics Office (NSO). (2018). 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census: Preliminary Report (Vol. 39, Issue 1).

http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/demography/census_2018/2018 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Report.pdf

Ngabo, F., Nguimfack, J., Nwaigwe, F., Mugeni, C., Muhoza, D., Wilson, D., Kalach, J., Gakuba, R.,Karema, C., & Binagwaho, A. (2012). Designing and implementing an innovative SMS-based alert system (RapidSMS-MCH) to monitor pregnancy and reduce maternal and child deaths in Rwanda. Pan African Medical Journal, 13(31). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2012.13.31.1864

Ngomane, S., & Mulaudzi, F. M. (2012). Indigenous beliefs and practices that influence the delayed attendance of antenatal clinics by women in the Bohlabelo district in Limpopo, South Africa.

Midwifery, 28(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.002

Noordam, C., Kuepper, B., Stekelenburg, J., & Milen, A. (2011). Improvement of maternal health services through the use of mobile phones. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 16(5),622–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02747.x NSO, & MACRA. (2014). National Survey on access to and usage of ICT services in Malawi.http://www.macra.org.mw/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Survey_on_Access_and_Usage_of_ICT_Services_2014_Report.pdf

Nyemba-Mudenda, M., & Chigona, W. (2018). mHealth outcomes for pregnant mothers in Malawi : a capability perspective. Information Technology for Development, 24(2), 245–278.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1397594

Patton, C., & Balakrishnan, P. V. S. (2010). The impact of expectation of future negotiation interaction on bargaining processes and outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 63(8), 809–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.07.002 Patton, C., & Sundar Balakrishnan, P. V. (2012). Negotiating when outnumbered: Agenda strategies for bargaining with buying teams. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(3), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.02.002

Pei, X., Chib, A., & Ling, R. (2022). Covert resistance beyond #Metoo: mobile practices of marginalized migrant women to negotiate sexual harassment in the workplace. Information Communication and Society, 25(11), 1559–1576.https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1874036

Prinja, S., Bahuguna, P., Gupta, A., Nimesh, R., Gupta, M., & Thakur, J. S. (2018). Cost effectiveness of mHealth intervention by community health workers for reducing maternal and newborn mortality in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 16(1), 1–19.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-018-0110-2

Rheault, M., & Mccarthy, J. (2016). Disparities in Cellphone Ownership Pose Challenges in Africa. GALLUP. https://news.gallup.com/poll/189269/disparities-cellphone-ownership-posechallenges-africa.aspx

Rogers, E. . (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Roloff, M. E., Putnam, L. L., & Anastasiou, L. (2003). Negotiation Skills. In Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills (Issue 1, pp. 801–833).

Sadki, S., & Bakkali, H. E. L. (2015). A Negotiation-based Approach to Resolve Conflicting Privacy Policies in M-Health. Journal of Information & Systems Management, 5(3), 91–105.

Schmidt, R. N., & Cross, B. E. (2014). The effects of auditor rotation on client management’s negotiation strategies. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(2), 110–130.https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-03-2013-0836

Seebregts, C., Tanna, G., Fogwill, T., Barron, P., & Benjamin, P. (2016). MomConnect: An exemplar implementation of the Health Normative Standards Framework in South Africa. South African

Health Review, 2016(1), 125–135. http://hdl.handle.net/10204/8657

Sondaal, S. F. V., Brown, J. L., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Borgstein, A., Miltenburg, A. S., Verwijs, M., & Klipstein-Grobusch, K. (2016). Assessing the effect of mHealth interventions in improving maternal and neonatal care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic

review. PLoS One, 11(5).

Sowon, K., & Chigona, W. (2021). Conceptualising healthcare-seeking as an activity to explain technology use - a case of mHealth. 1st Virtual Conference on Implications of Information and Digital Technologies for Development, 836–852.

Sowon, K., Maliwichi, P., & Chigona, W. (2022). The Influence of Design and Implementation Characteristics on the Use of Maternal Mobile Health Interventions in Kenya: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 10(1), e22093. https://doi.org/10.2196/22093

Tran, M., Labrique, A., Mehra, S., Ali, H., Shaikh, S., Mitra, M., Christian, P., & West Jr, K. (2015). Analyzing the Mobile “Digital Divide”: Changing Determinants of Household Phone Ownership Over Time in Rural Bangladesh. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 3(1), e24.

https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3663

Vickery, J. R. (2015). ‘I don’t have anything to hide, but … ’: the challenges and negotiations of social and mobile media privacy for non-dominant youth. Information Communication and Society, 18(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.989251 VillageReach. (2017). A national mobile health hotline in Malawi: One step closer.

https://www.villagereach.org/2017/07/22/digital-health-innovation-last-mile-sustainabilitypartnership/#:~:text=I am pleased to announce,mobile health hotline in Africa.

VillageReach. (2018). Press Release:National expansion plan for Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF): A health and nutrition hotline. http://www.villagereach.org/press-release-national-expansion-planchipatala-cha-pa-foni-ccpf-health-nutrition-hotline/

Watkins, S. C., Robinson, A., & Dalious, M. (2013). Evaluation of the Information and Communications Technology for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Project http://www.villagereach.org/wpcontent/

uploads/2017/07/ICT_for_MNCH_Report_131211md_FINAL.pdf

WHO. (2012). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO.

WHO. (2014). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013 (Estimates By WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA,

The World Bank, United Nations Population Division). WHO.

https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2013/en/WHO. (2015). A practical guide for engaging with mobile network operators in mHealth for reproductive , maternal , newborn and child health. WHO.

Willcox, M., Moorthy, A., Mohan, D., Romano, K., Hutchful, D., Mehl, G., Labrique, A., & LeFevre,A. (2019). Mobile technology for community health in Ghana: Is maternal messaging and provider use of technology cost-effective in improving maternal and child health outcomes at

scale? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/11268

Zamani, E. D., & Sbaffi, L. (2020). Embracing uMunthu: How Informal Caregivers in Malawi Use ICTs. In J. . Bass & P. . Wall (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Development. ICT4D 2020. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol

587 (pp. 93–101). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65828-1_8

Zohar, I. (2015). “The Art of Negotiation” Leadership Skills Required for Negotiation in Time of Crisis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 540–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.285